Just before London went into lockdown during the pandemic, I flounced out of a job working at a specialist perfume boutique. During my time there, one of the most common questions I was asked by young women looking for a new fragrance was my recommendation for a sexy scent.

For me, that’s an impossible question to answer. Not only is it too subjective, but I also dislike the idea of wearing perfume for the pleasure of others. Admittedly, there is a certain public service element to dousing oneself in a stunning fragrance (especially when it’s been purchased from Sainte Cellier!); but the most attractive perfumes are the ones that make us feel more confident and empowered, which are both always sexy. That was always how I answered that question.

But what does it mean to smell sexy? Who decides? Sexy for whom? Yes, it’s a subjective question, but one the perfume industry has never shied away from answering on behalf of women. Perfume has long been sold as part of a woman’s arsenal of attraction. Glossy ads promising seduction date back decades. Sexy becomes a commodity, shaped less by personal feeling and more by cultural expectation.

And within those expectations lie the regimented beauty standards for women inside a system that rewards and protects certain performances of femininity tied to youth, thinness, whiteness, cisnormativity and wealth. To be desirable in our society is often to be granted access. To be considered worthy of attention, protection or love. The flip side is brutal. Not conforming to the dictates of desirability can be a sentence to invisibility or worse.

For trans women, this negotiation can be particularly acute. It’s a life-shaping pressure where something as ordinary as using a public restroom becomes a site of risk. Cis women, too, perform a version of this high-wire act. For them, it is less about actual safety and more about acceptability, or more precisely, respectability. Worth is often gauged through impossible expectations: to be beautiful but effortless, desirable but modest, visible but not too loud. These demands, maintained by whims as shifting as hemlines, remain just out of reach, creating a feedback loop of failure. Across both trans and cis experience, the blueprint of womanhood we’re all held up against has been sculpted by male desire.

From the Ancien Régime’s extravagant silhouettes of heaving busts, corseted waists and hips ballooned to comic proportions with panniers to Dior’s post-war New Look, which cinched women back into appetite-worthy hourglasses just as the world emerged sex-starved from war, the fantasy of femininity has almost always been dressed (or undressed) for consumption. Today’s surgically sculpted forms may be glossier, but they echo the same pattern of bodies shaped to satisfy the eye.

These looks may seem excessive or artificial to some, but in a culture that rewards a particular kind of curated, consumable femininity, it’s also a form of self-protection. Aesthetic conformity becomes strategy.

Of course not every nip, tuck and rejuvenation is an existential consideration, especially when performed with the cocoon of extreme wealth. But even at the highest rungs of privilege, the pressure to embody a legibly desirable ideal remains. In a world fed on performance and digital spectatorship, the body becomes an offering. Sometimes to a billionaire husband. Sometimes to millions of scrolling strangers. The cost may shift, but the implicit currency never does.

To lambast a woman for that choice without interrogating the system that necessitates it is yet another form of misogyny. We cannot continue to place women in dynamics where they are both damned if they do and damned if they don’t.

And this is where the question of agency becomes crucial. In a world that constantly scripts what women should want, and how they should appear while wanting it, exercising desire outside of those scripts becomes a radical act. To choose one's aesthetic, one's scent, one's presentation for oneself is an assertion of autonomy. Whether that choice aligns with the mainstream or disrupts it entirely isn’t the point. It matters that the choice is made, not imposed.

Belle de Jour, the film that inspired ERIS Parfums’ fragrance of the same name, is a work concerned with agency. Or perhaps more accurately, a film where a woman dares to seize it in her own conflicted, compartmentalised way.

Catherine Deneuve’s Séverine is not a symbol of rebellion in the traditional sense. She isn’t loud, confrontational or overtly transgressive. Her resistance is quieter, stranger, stitched into secrecy. A bourgeois housewife who begins working at a brothel on her afternoons, Séverine enters a double life not out of desperation, but desire. Her choices are difficult to explain, perhaps even to herself. And that’s part of the point. Her sexual autonomy doesn’t conform to the limits of how society defines femininity, respectability or pleasure. But it’s hers.

And in a world that demands women be either saint or siren, respectable or ruined, Belle de Jour suggests another path. One that’s murkier, messier, but ultimately more honest. It’s not a clean narrative of liberation. But it is a portrayal of a woman who takes the reins of her longing.

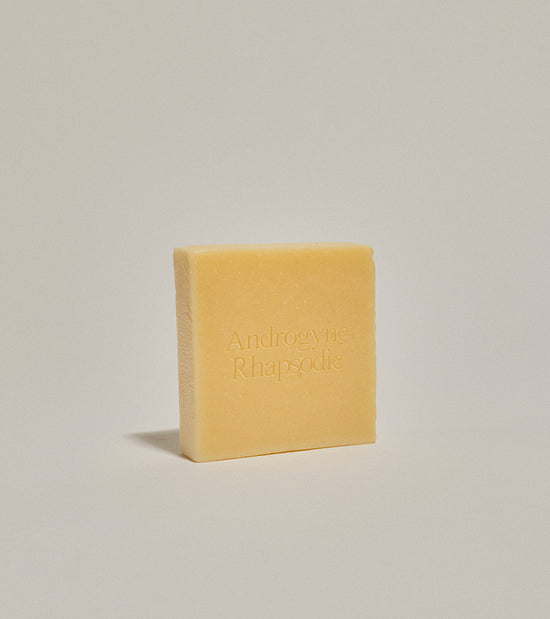

ERIS’s Belle de Jour is a perfume that feigns an attempt at cleanliness, but with the insouciance of an unrepentant sinner flossing with rosary beads. Its top notes, crowned in soapy coriander, mirror the refreshening crispness of a traditional cologne, but it ultimately embraces its salt-licked skin. This is skin after hungry kisses. After breath caught in the throat. After the slow-flood heat of surrender. It’s tangled limbs and creeping sweat, fleshy crevices flushed with want.

It begins with the illusion of purity, but never forgets the body. That duality is what gives the perfume its charge, captured so adroitly in perfumer Antoine Lie’s inspired use of jasmine, a flower that inherently walks the tightrope between innocence and indecency, alongside seaweed absolute, brackish and bodily and the hot-flesh hum of Atlas cedarwood. Together, they sketch a scent that refuses to be scrubbed clean of its own desire.

Aesthetically speaking, Belle de Jour kills two birds with one stone. Its angular, salt-licked profile stands in direct opposition to the tsunami of cloying, sugar-rush feminine scents flooding the mainstream. Perfumes engineered to be pleasing, pretty, safe. They wipe away shadow, sharpness and depth. They smell like they’re asking for permission.

Belle de Jour refuses all of that.

It also subverts the so-called “clean girl” aesthetic and all its racialised and classist implications by tossing aside the desire to be clean entirely. Whatever crispness it offers at first doesn’t last. The scent dives, unapologetically, into something far messier. Heat-slick skin and satisfied hunger. The scent of glowing aftermath.

Luxury, to me, isn’t just in rare ingredients or prestige pricing. It’s in the space a perfume gives your imagination to roam. The ability to slip into another skin, another story, even just for a moment. Perfume is the air that fantasy breathes. And Belle de Jour allows for seriously deep breaths.

In a world that worships clarity, efficiency and control, that kind of fantasy isn’t just indulgent. It’s radical freedom worn on your skin.