In this essay, Jessica takes a close look at a rare ideal union of fragrance and fashion.

When Alexander McQueen launched his first fragrance in 2003, he was already famed as one of Britain’s most creative and transgressive fashion designers. His graduation collection at London’s Central Saint Martins was titled “Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims,” and after founding his own brand in 1992, he released collections with such inspirations as Stephen King’s The Shining, psychiatric hospitals, and bullfights. When his foray into fragrance was announced, fashion and fragrance fans may have wondered how his designs, with their references to sadomasochism and Scottish tartans, taxidermy and Taxi Driver, would translate into perfumery.

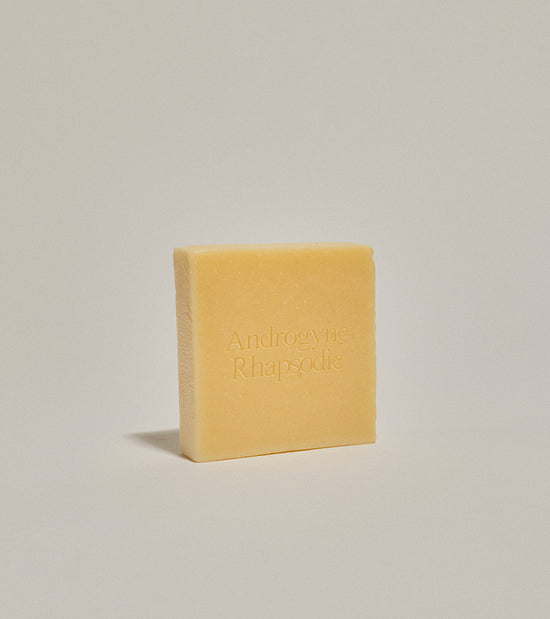

One reporter had actually asked McQueen in 1996 whether he would ever sell a perfume under his name. “Yeah…Eau de Scat,” the designer answered, with his typically wicked sense of humor. The perfume released as Kingdom in March 2003 (through a license with YSL Beauté) couldn’t exactly be described as fecal, but it was still a departure from the sweet-and-fruity celebrity scents proliferating on Sephora’s shelves at that time. McQueen said his brief for perfumer Jacques Cavallier-Belletrud asked for a scent “verging on androgyny, one that moves between the feminine and masculine.” The result was a dense, jasmine-heavy floral tinged with notes of raw, almost dirty, resins and spices—including cumin, which can give an impression of unwashed bodies. Whether or not Cavallier-Belletrud knew that McQueen was a fan of Patrick Suskind’s novel Perfume (1985), with its theme of murderous obsession and its shockingly carnal conclusion, he had developed a scent that was suitably provocative.

Kingdom’s bottle was also a fitting extension of McQueen’s design aesthetic. Created by industrial designer Patrick Veillet and produced by metalware manufacturer Guy Degrenne, it was a sleek object that could be laid down at various angles, a combination of convex and flat surfaces, of reflective and refractive materials. The bottle’s outline also echoed a headpiece from McQueen’s Winter 1998 collection, “Joan,” an homage to Joan of Arc, the peasant girl who went to battle for her faith. Its stainless-steel outer layer was hinged so it could open and close like a visor, concealing or revealing the inner bottle’s blood-red glass heart.

Veillet has since revealed, via social media, that his source materials for the Kingdom bottle included a suit of medieval armor and the heart-shaped face of a barn owl. This contrast between steely and soft, manufactured and natural, matched McQueen’s philosophy. McQueen himself had said, “When you see a woman wearing McQueen, there’s a certain hardness to the clothes that makes her look powerful…It kind of fends people off.” At the same time, he acknowledged the sensitivity underlying his affinity for the macabre: “I am a melancholy type of person. I’m feeling, deep, and romantic at heart and this fragrance comes from my heart,” he said at the press event for Kingdom’s launch. He also mentioned the poem he had commissioned from writer Jorie Graham, a verse with what he called “an Edgar Allan Poe feeling to it,” to be inscribed on Kingdom’s packaging---one line was “Pierce my heart, again.”

Kingdom’s regal title played on the “queen” already present within the designer’s surname and may have alluded to his ever-expanding success as well as the fantasy and prestige he offered his customers. However, a happy ending eluded McQueen himself. After his death by suicide in 2010, several of McQueen’s friends commented on his struggles with intimacy. The emotional scars of childhood sexual abuse, an HIV-positive diagnosis, and grief over the deaths of his muse Isabella Blow and his mother Joyce all contributed to a sense of isolation, exacerbated by heavy drug use, even as his fashion career soared.

Kingdom was discontinued after just a few years, due to low sales; it was too challenging a fragrance for a mainstream audience. But its packaging resurfaced in 2011, in the retrospective exhibition Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, held at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. There, amongst a display of accessories in a room titled “Cabinet of Curiosities,” two Kingdom bottles glowed under gallery lighting in the company of a chain mail headdress, a red glass cuirasse, a bracelet resembling a twist of gleaming barbed wire (by the jeweler Sean Leane), and a medieval-inspired helmet and armor sleeve (by Sarah Harmarnee). Talismans, jewelry, or defenses against enemies? Many of McQueen’s accessory collaborations, including the Kingdom bottle, were all of the above.

When asked in a 2004 interview what made his own heart skip a beat, McQueen replied, “Falling in love.” He had often said that his collections were autobiographical; through Kingdom, as well, he may have been recognizing our need to express our earthier desires and yet to shield our fragile, radiant hearts. Kingdom, like so much of McQueen’s work, was an uncanny manifestation of the impulses that rule us.

Notes

“Eau de Scat”: “The McQueen of England,” Women’s Wear Daily, 28 March 1996.

“Verging on androgyny”: “Kingdom Come,” WWD, January 10, 2003.

“When you see a woman wearing McQueen”: Jess Carter-Morley, “Boy Done Good,” The Guardian (London), September 19, 2005.

“I am a melancholy type of person”: WWD, January 10, 2003.

“My collections”: Harriet Quick, “Killer McQueen,” Vogue (London), October 2002.

“An Edgar Allan Poe feeling,” WWD, January 10, 2003.

“Falling in love:” “Meeting the Queen was like falling in love,” The Guardian (London), April 20, 2004.

Jessica Murphy is a museum professional with a passion for perfume. She writes at Now Smell This and her own blog, Perfume Professor, and she frequently lectures on the history of fragrance. She is currently working on a study of perfume bottles.

She posts at Instagram @tinselcreation.