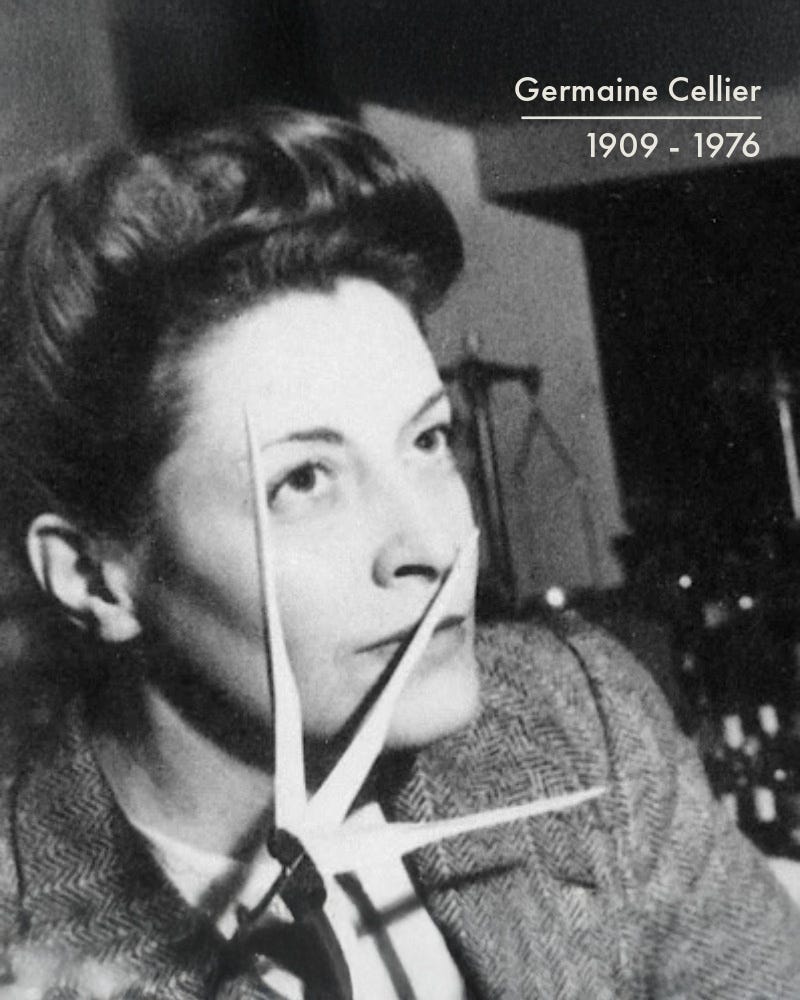

I named Sainte Cellier in honour of Germaine Cellier, the iconoclast perfumer whose work spoke to me before I even knew her name.

In my early twenties, I was devoted to Fracas, which began a love affair with tuberose that lasted well into my thirties. Later, when I discovered that Cellier was its creator, along with Bandit, Vent Vert, and a handful of other radically inventive perfumes, I began studying her work more closely.

Her perfumes go beyond just smelling good. To me, they always feel like they have something to say. If perfume can be held up as a mirror to its epoch, Cellier’s scents seem to overflow with cultural and societal commentary.

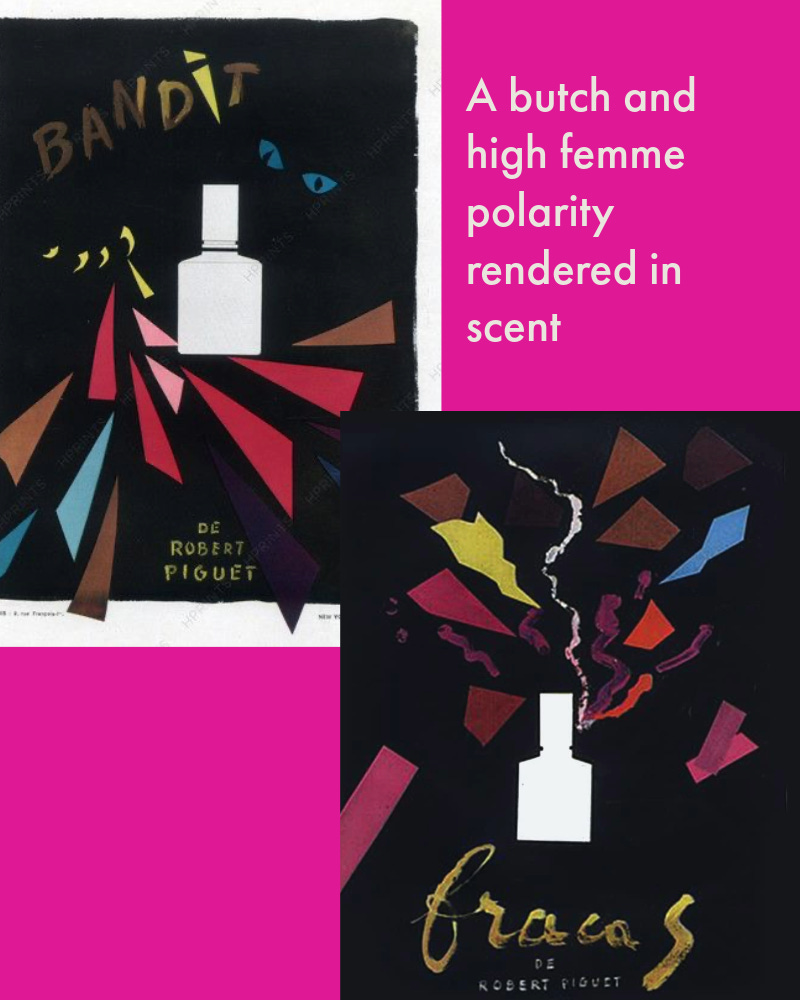

Bandit, released in 1944, was leather-clad rebellion in a bottle: queer, angular, and unapologetically subversive. Fracas turned the dial up on femininity to the point of weaponisation, with its tuberose-crowned white floral bouquet, ripe peach flesh, and smouldering musks.

Together, they formed an olfactory dyad. One spiky, one lush. A butch and high femme polarity rendered in scent, unfolding across a world still raw from war.

Pierre Balmain’s Jolie Madame (1953) is the only perfume composed by Germaine Cellier released in the 1950s.

It’s often described as a violet leather chypre, but that barely touches its emotional terrain. Jolie Madame is sharp, restrained and pointed. Behind its perfectly manicured structure lies a dangerous stifled rage.

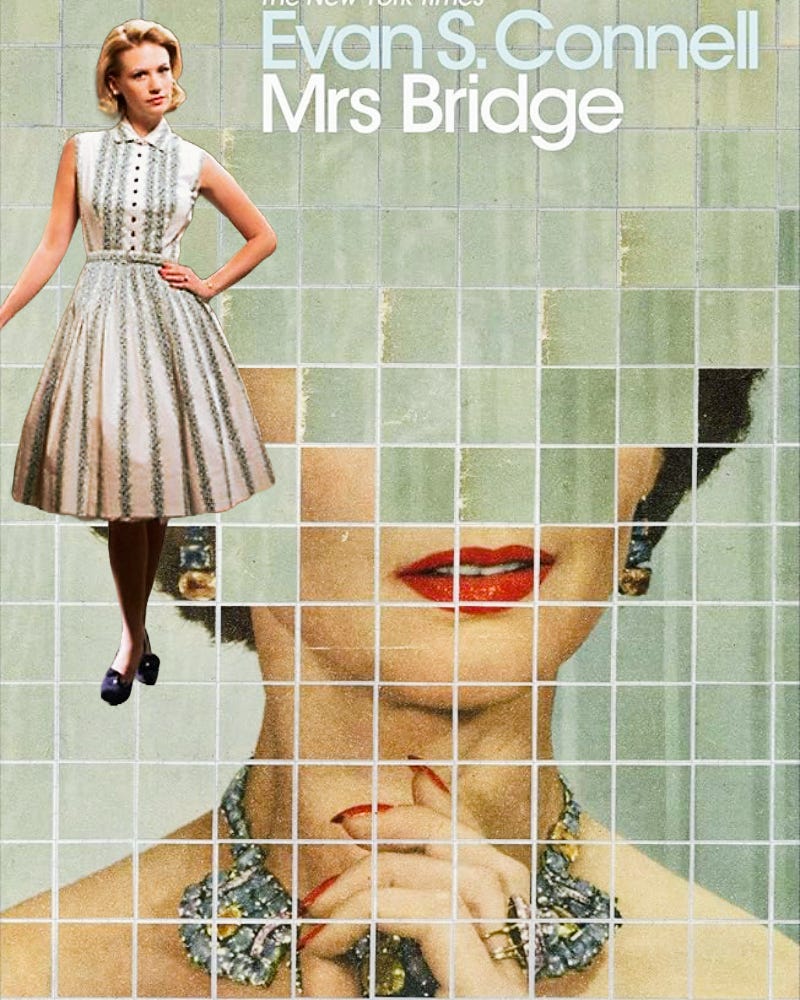

This was the age of the midcentury ideal. The return to domesticity. The sculpted housewife. The smile that never quite reached the eyes. But Jolie Madame doesn’t simply play that role. It critiques it from within.

Cellier subverts the usual delicate treatment of violet by turning it into something taut and unsentimental. It’s not soft. It’s sharp. Tightly wound. The leather here isn’t buttery or warm. It’s closer to bondage. Restrictive. Intentionally uncomfortable.

There’s a cultivated perfection to it. Something too composed, too deliberate. Like a woman trained not just to smile, but to never let the corners slip. It reminds me of characters like Betty Draper in Mad Men, or India Bridge in Mrs. Bridge, the 1959 novel by Evan S. Connell. These are women fluent in a performance no one truly enjoys, but everyone sustains. They move through a world built on appearances, silences, swallowed words and beautifully suppressed discontent.

Which brings me to Pistil, a contemporary perfume by Marie-Pierre Blanchette of Miskeo Parfums that I carry at Sainte Cellier. Pistil is a descendent of Jolie Madame by way of Peter Weir’s 1975 Picnic at Hanging Rock.

The atmosphere of that film, with its lush, dreamlike pacing and eerie sensuality, feels deeply aligned with Pistil’s quietly subversive emotional world. There’s something unmistakably queer in the gaze, in the way mystery, repression, and tenderness intertwine. The lace collars. The girls disappearing into the wild. The tight-laced Victorian order slowly, inevitably, falling apart.

If Jolie Madame is the polished surface of midcentury constraint, then Pistil is what happens when that surface is allowed to crack.

Where Jolie Madame remains tightly constrained, caged in composure, Pistil lets it fall open into something more spectral. A haze of half-remembered swooning skin and the flowers that bloomed within.

Pistil isn’t a reinterpretation of Jolie Madame. It’s a descendent. Not in structure, but in spirit. It carries the same violet thread, but where Jolie Madame keeps it bound in leather and control, Pistil lets it blur. The animalic hum of costus flickers underneath. Musky, intimate, a little unwashed. Like rebellion that’s made itself at home in the body.

To me, Pistil feels like the part of Jolie Madame she couldn’t fully express. The private ache beneath the pose. The wish she never never uttered out loud.

Pistil is by no means a modernisation of Jolie Madame. The tension, the simmering malice that pulses through Jolie Madame’s carefully composed body, is what makes it such a compelling perfume for me.

But Pistil can be seen as a continuation of the conversation. A loosening of the stays. A reframe of what may once have read as prim, conservative, WASP-coded femininity. Now glowing with intimacy, flower porn, and post-coital skin.

Two violets, generations apart. One constrained. One dissolving.

Both, in their own way, acts of resistance.